By Kim Zetter and Kevin Poulsen

By Kim Zetter and Kevin Poulsen

A U.S. Army intelligence analyst suspected of leaking videos and documents to Wikileaks was charged Monday with eight violations of federal criminal law.

Charges included unauthorized computer access, and a single count of transmitting classified information to an unauthorized third party.

Pfc. Bradley Manning, 22, was charged with two counts under the Uniform Code of Military Justice: one encompassing the eight alleged criminal offenses, and a second detailing four noncriminal violations of Army regulations governing the handling of classified information and computers.

According to the charge sheet, Manning downloaded a classified video of a military operation in Iraq and transmitted it to a third party, in violation of a section of the Espionage Act, 18 U.S.C. 793(e), which involves passing classified information to an uncleared third party, but not a foreign government.

The remaining criminal charges are for allegedly abusing access to the Secret-level SIPR network to obtain more than 150,000 U.S. State Department cables, some of them classified, as well as an unspecified classified PowerPoint presentation.

With regard to the State Department cables, Manning allegedly passed more than 50 classified cables to an unauthorized party but downloaded at least 150,000 nonclassified State Department documents, according to Army spokesman Lt. Col. Eric Bloom. These numbers could change as the investigation continues, Bloom said.

Between Jan. 13 and Feb. 19 this year, Manning allegedly passed one of the cables, titled “Reykjavik 13,” to an unauthorized party, the Army states. The Army doesn’t name Wikileaks as the recipient of the document, but last February the site published a classified cable that describes a U.S. embassy meeting with the government of Iceland.

If convicted of all charges, Manning could face a prison sentence of as much as 52 years, Bloom said.

Manning was put under pretrial confinement at the end of May, after he disclosed to a former hacker that he was responsible for leaking classified information to Wikileaks. He’s currently being held at Camp Arifjan in Kuwait and has been assigned a military defense attorney, Capt. Paul Bouchard, who was not available for comment. Bloom said that Manning has not retained a civilian attorney, though Wikileaks stated recently that it commissioned unnamed attorneys to defend the soldier.

The next step in Manning’s case is an Article 32 hearing, which is an evidentiary hearing similar to a grand jury hearing, to determine if the soldier should be court-martialed.

Manning, who comes from Potomac, Maryland, enlisted in the Army in 2007 and was an Army intelligence analyst who was stationed at Forward Operating Base Hammer 40 miles east of Baghdad, Iraq, last November. He held a Top Secret/SCI clearance.

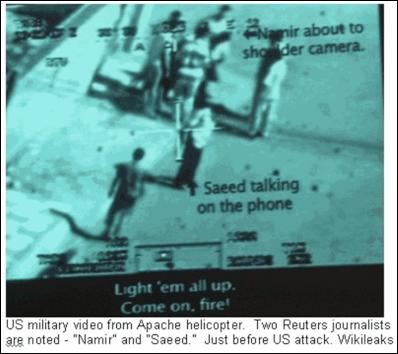

In May, he began communicating online with a former hacker named Adrian Lamo. Very quickly in his exchange with the ex-hacker, Manning disclosed that he was responsible for leaking a headline-making Army video to Wikileaks. The classified video, which Wikileaks released April 5 under the title “Collateral Murder,” depicted a deadly 2007 U.S. helicopter air strike in Baghdad on a group of men, some of whom were armed, that the soldiers believed were insurgents.

The attack killed two Reuters employees and an unarmed Baghdad man who stumbled on the scene afterward and tried to rescue one of the wounded by pulling him into his van. The man’s two children were in the van and suffered serious injuries in the hail of gunfire.

Manning also said he leaked a separate video to Wikileaks showing the notorious May 2009 air strike near Garani village in Afghanistan that the local government says killed nearly 100 civilians, most of them children. The Pentagon released a report about the incident last year, but backed down from a plan to show video of the attack to reporters.

Other classified leaks he claimed credit for included an Army document evaluating Wikileaks as a security threat and a detailed Army chronology of events in the Iraq war. But the most startling revelation was a claim that he gave Wikileaks a database of 260,000 classified U.S. diplomatic cables, which Manning said exposed “almost-criminal political back dealings.”

“Hillary Clinton and several thousand diplomats around the world are going to have a heart attack when they wake up one morning, and find an entire repository of classified foreign policy is available, in searchable format, to the public,” Manning told Lamo in an online chat session.

Manning anticipated watching from the sidelines as his action bared the secret history of U.S. diplomacy around the world.

“Everywhere there’s a U.S. post, there’s a diplomatic scandal that will be revealed,” Manning wrote of the cables. “It’s open diplomacy. Worldwide anarchy in CSV format. It’s Climategate with a global scope, and breathtaking depth. It’s beautiful, and horrifying.”

Wikileaks has acknowledged possessing the Afghanistan video and representatives of the organization indicated in media interviews that it will release the video soon. The organization has denied that it received 260,000 classified cables.

In his chats with Lamo, Manning discussed personal issues that got him into trouble with his Army superiors and left him socially isolated, and said he had been demoted and was headed for an early discharge from the military.

He claimed to have been rummaging through classified military and government networks for more than a year and said the networks contained “incredible things, awful things … that belonged in the public domain, and not on some server stored in a dark room in Washington, D.C.”

Manning discovered the Iraq video in late 2009, he said. He first contacted Wikileaks founder Julian Assange sometime around late November last year, he claimed, after Wikileaks posted 500,000 pager messages covering a 24-hour period surrounding the Sept. 11 terror attacks. ”I immediately recognized that they were from an NSA database, and I felt comfortable enough to come forward,” he wrote to Lamo.

In January, while on leave in the United States, Manning visited a close friend in Boston and confessed he’d gotten his hands on unspecified sensitive information, and was weighing leaking it, according to the friend. “He wanted to do the right thing,” 20-year-old Tyler Watkins told Wired.com. “That was something I think he was struggling with.”

Manning passed the video to Wikileaks in February, he told Lamo. After April 5 when the video was released and made headlines, Manning contacted Watkins from Iraq asking him about the reaction in the United States.

“He would message me, ‘Are people talking about it?… Are the media saying anything?’” Watkins said. “That was one of his major concerns, that once he had done this, was it really going to make a difference?… He didn’t want to do this just to cause a stir…. He wanted people held accountable and wanted to see this didn’t happen again.”

Lamo decided to turn in Manning after the soldier told him that he leaked a quarter-million classified embassy cables. Lamo contacted the Army, and then met with Army CID investigators and the FBI to pass the agents a copy of the chat logs from his conversations with Manning. At their second meeting with Lamo on May 27, FBI agents from the Oakland Field Office told the hacker that Manning had been arrested the day before in Iraq by Army CID investigators.

As described by Manning in his chats with Lamo, his purported leaking was made possible by lax security online and off.

Manning had access to two classified networks from two separate secured laptops: SIPRNET, the Secret-level network used by the Department of Defense and the State Department, and the Joint Worldwide Intelligence Communications System which serves both agencies at the Top Secret/SCI level.

The networks, he said, were both “air gapped” from unclassified networks, but the environment at the base made it easy to smuggle data out.

“I would come in with music on a CD-RW labeled with something like ‘Lady Gaga,’ erase the music then write a compressed split file,” he wrote.

“No one suspected a thing and, odds are, they never will.”

“[I] listened and lip-synced to Lady Gaga’s ‘Telephone’ while exfiltrating possibly the largest data spillage in American history,” he added later.

”Weak servers, weak logging, weak physical security, weak counterintelligence, inattentive signal analysis … a perfect storm.”

Manning told Lamo that the Garani video was left accessible in a directory on a U.S. Central Command server, centcom.smil.mil, by officers who investigated the incident. The video, he said, was an encrypted AES-256 ZIP file.

This article first appeared on Truthdig.com.