The US government must release its estimates of how many people are being killed in CIA drone strikes, to end an over-reliance on often scanty media reports, a new study on drone casualties says.

The absence of ‘hard facts and information that should be provided by the US government’ means that the public debate is dependent on estimates of casualties provided by organisations including the Bureau, academics at Columbia University Law School’s Human Rights Clinic said. This risks masking the ‘true impact or humanitarian costs’ of the campaign, they added.

The study also found that the two US-based monitoring organisations, the Long War Journal and the New America Foundation – have been under-recording credible reports of drone civilian casualties in Pakistan by a huge margin.

When all credible reports of casualties for the year 2011 were examined, only the Bureau was found to properly reflect the number of civilians reported killed.

Counting Drone Strike Deaths is the second report to be released within weeks by Columbia University Law School. Its previous report examined the impact on civilians of US drone campaigns in Yemen, Somalia and Pakistan.

Counting Drone Strike Deaths examined the Bureau’s database of drone strikes in Pakistan alongside the work of two other organisations that track drone strikes and their reported casualties, the Long War Journal and the New America Foundation. Each of the three gathers media reports of particular strikes and keeps a running tally of casualties.

The Bureau’s data ‘appears to have a more methodologically sound count of civilian casualties’

The work of all three has ‘permeated and significantly impacted debate’ in the past year. However the Human Rights Clinic found the Long War Journal and New America Foundation both ‘significantly undercount’ civilian deaths.

Such underestimates carry real risk, the report said: ‘they may distort our perceptions and provide false justification to policymakers who want to expand drone strikes to new locations, and against new groups’.

And the report warned media organisations against regularly citing data from either New America Foundation or the Long War Journal: ‘Exclusive or heavy reliance on the casualty counts of these two organisations is not appropriate because of the significant methodological flaws we identify,’ it states.

Missing casualties

Researchers examined every drone strike reported in 2011, and compared the datasets of each of the three organisations with the available English-language media reports.

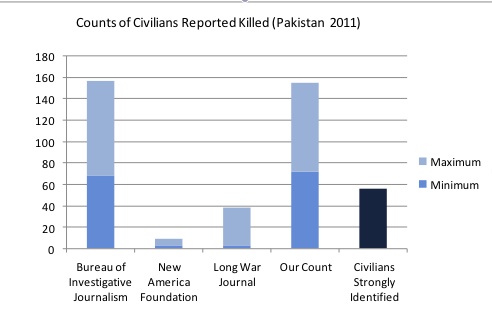

The Human Rights Clinic found that according to the available reporting, between 72 and 155 civilians were credibly reported killed by drone strikes in 2011.

The New America Foundation, which is widely cited by many US media organisations, reported only that between three and nine civilians had been killed in the same period – an underestimate of 2,300%, according to the researchers. And the Long War Journal counted 30 civilians killed. By contrast the Bureau’s minimum estimate of 68 civilian deaths was significantly closer.

The Bureau’s data ‘appears to have a more methodologically sound count of civilian casualties’ due to using more sources than other organisations, employing field researchers to corroborate accounts on the ground and updating its data on individual strikes when new information emerges, the report said.

But there are inherent problems with relying predominantly on media reporting that apply to the Bureau’s work as much as to the New America Foundation’s or the Long War Journal’s. The tribal region of Waziristan, where the vast majority of strikes take place, is notoriously difficult for reporters to access: much reporting relies on stringers or conversations with locals.

The New America Foundation, which is widely cited by many US media organisations, found between three and nine civilians had been killed in the same period – an underestimate of 2,300%, according to the researchers. And the Long War Journal counted 30 civilians killed. By contrast the Bureau’s minimum estimate of 68 civilian deaths was significantly closer.

Only a handful of incidents are reported in any kind of depth – usually those where a highly ranked militant leader has been killed or there was a particularly heavy loss of life, the report’s authors note. Most strikes are only reported in very basic terms, and it’s not uncommon for reports to contradict one another, including in the number of people reported killed. Quotes confirming strikes usually come from anonymous locals or officials – who may have their own motivations for describing the dead as militants or civilians.

And the term ‘militant’ is dangerously ambiguous, the report’s authors add: the US has provided no legal definition, although in May it emerged that the US administration classifies all Waziri men of fighting age as militants. Only the Bureau consistently uses the term ‘alleged militant’ in its reporting – a policy the study suggests that other organisations adopt.

All of this means that the counts provided by the Bureau and similar organisations are ‘estimates, not actual body counts’. Yet there is a danger that such estimates are ‘assimilated into fact, they threaten to become what everybody knows about the US drone strikes program’, the report says – when in fact no such certainty exists. They risk becoming an ‘inadequate’ and even ‘dangerous’ substitute for official figures.

On October 30 2011, missiles fired by a drone hit a vehicle and, according to some reports, a house in Dattakhel, North Waziristan. While anonymous officials said the dead were all militants, unnamed locals insisted they were civilians, and that four of them were chromite miners, naming one of them as Saeedur Rahman, a chromite dealer. But the Bureau, the New America Foundation and the Long War Journal’s accounts of the incident tell three different stories.

The New America Foundation reported that 3-6 ‘unknowns’ had died, citing six sources, while the Long War Journal reported that six ‘militants’ had died, based on two reports.

But looking at 12 sources, the Bureau reported that 4-6 people had been killed including four civilians. In March 2012 the New York Times published an investigation into the strike naming three more of the dead and repeating the claim that they were chromite miners; the Bureau incorporated the names into its data.

The report’s authors agreed with the Bureau’s assessment that 4-6 died including four civilians, and said the identification of the remaining two was ‘weak’ as it was only confirmed by anonymous officials. Meanwhile, multiple sources suggested four of the dead were miners.

US officials have been keen to hold up the drone programme as a great success, the report’s authors note, while claiming that to release estimates of the numbers killed would jeopardise US security. But it has previously released similar information for Afghanistan without issue.

Chris Woods, who leads the Bureau’s drones investigation team, welcomed the Columbia findings. US monitoring groups have been significantly under-reporting credible counts of civilian deaths for some time, he said, which had been distorting public understanding of the impact of the US bombing campaign in Pakistan.

‘While the Bureau’s drones data is clearly shown to be the most accurate reflection of what’s publicly known about the drone strikes, both by the Columbia study and the recent Stanford/ NYU report, there is an urgent need for the US to publish its own estimates of who it is killing in Pakistan and elsewhere.’

Read Counting Drone Strike Deaths

This article originally appeared on the site of the Bureau of Investigative Journalism.

by

by