What is the government doing? Last year, when Congress passed the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), with its contentious passages endorsing the mandatory military detention of terror suspects, there was uproar across the political spectrum from Americans who believed that it would be used on US citizens.

In fact, it was unclear whether or not this was the case. The NDAA was in many ways a follow-up to the Authorization for Use of Military Force, passed by Congress the week after the 9/11 attacks, which authorized the President “to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons, in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons.”

As confirmed by the Supreme Court in June 2004, in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, the NDAA also allowed those seized — who were allegedly involved with al-Qaeda and/or the Taliban — to be held until the end of hostilities. The AUMF was, and remains the basis for the detention of prisoners at Guantánamo, but on two occasions President Bush decided that it applied to US citizens — in the cases of Jose Padilla and Yaser Hamdi, who were held on US soil as “enemy combatants” and subjected to torture.

When challenged in court, however, President Bush never attempted to defend holding US citizens without charge or trial, transferring Padilla to the federal court system, and sending Hamdi back to Saudi Arabia, where he had lived for many years before his capture in Afghanistan and his initial transfer to Guantánamo. In the case of the legal US resident Ali al-Marri, a third man held as an “enemy combatant” on the US mainland, and also subjected to torture, President Bush avoided making a decision about him, and it was left to President Obama, who transferred him into the federal court system soon after taking office in January 2009.

If the muddled nature of these precedents made it difficult to establish whether or not the new legislation applied to US citizens as well as foreigners, the changes in wording from the AUMF were also inconclusive. Section 1021 was similar to the AUMF in that it applies to anyone “who planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored those responsible for those attacks,” but it also expanded the AUMF’s remit, stating explicitly that the military custody provisions also apply to anyone “who was a part of or substantially supported al-Qaeda, the Taliban, or associated forces that are engaged in hostilities against the United States or its coalition partners, including any person who has committed a belligerent act or has directly supported such hostilities in aid of such enemy forces.”

The problem, as anyone capable of looking at the legislation objectively has realized, is that the “associated forces” included with al-Qaeda and the Taliban are not defined, and could, therefore, be applied to anyone regarded as a threat, who could, however tangentially, be claimed to be associated with al-Qaeda and/or the Taliban. As the New York Times explained last week, the NDAA’s enactment “was controversial in part because lawmakers did not specify what conduct could lead to someone’s being detained, and because it was silent about whether the statute extended to American citizens and others arrested on United States soil.”

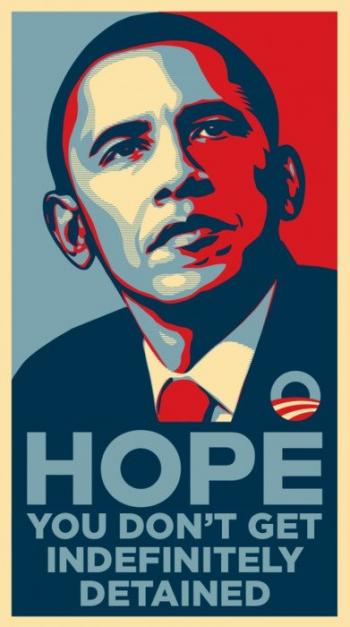

When President Obama signed the NDAA into law on December 31 last year, he tried to allay fears about the military detention provisions. He claimed that Section 1021 “breaks no new ground and is unnecessary,” because “[t]he authority it describes was included in the 2001 AUMF [the Authorization for Use of Military Force], as recognized by the Supreme Court and confirmed through lower court decisions since then.”

He also sought to reassure those who feared that the provisions might be applied to US citizens, stating, “I want to clarify that my Administration will not authorize the indefinite military detention without trial of American citizens. Indeed, I believe that doing so would break with our most important traditions and values as a Nation.”

However, after the President signed the NDAA into law, a number of journalists and activists decided to test whether or not he was being truthful, as they feared that the NDAA’s military custody provisions were, in fact, far more sweeping than the AUMF, and that “associated forces” could include Americans, and could include journalists and activists. The lead plaintiff was the journalist Chris Hedges, and others included Noam Chomsky, Daniel Ellsberg, the Icelandic parliamentarian and WikiLeaks activist Birgitta Jónsdóttir, Kai Wargalla, one of the founders of Occupy London, and the US journalists and activists Tangerine Bolen and Alexa O’Brien.

In May, as I explained here, Hedges and co. won a resounding victory, when, in the District Court in New York, Judge Katherine Forrest struck down, through an injunction, Section 1021 of the NDAA, agreeing with the plaintiffs that it was “constitutionally infirm, violating both their free speech and associational rights guaranteed by the First Amendment as well as due process rights guaranteed by the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution.”

Judge Forrest’s actions were not permanent. Technically, as she explained in her ruling, she “preliminarily enjoin[ed] enforcement of §1021 pending further proceedings in this Court or remedial action by Congress mooting the need for such further proceedings,” and those further proceedings led, last week, to another landmark ruling, when, responding to further submissions by both parties over the last four months, she again sided with the plaintiffs, issuing a permanent injunction on Section 1021 of the NDAA, and explaining why:

The due process rights guaranteed by the Fifth Amendment require that an individual understand what conduct might subject him or her to criminal or civil penalties. Here, the stakes get no higher: indefinite military detention — potential detention during a war on terrorism that is not expected to end in the foreseeable future, if ever. The Constitution requires specificity — and that specificity is absent from §1021(b)(2). [the key passage that includes “associated forces”].

And yet, despite President Obama’s supposedly soothing statements in December, the administration responded to Judge Forrest’s ruling with hysteria, issuing an emergency appeal, and arguing that her injunction “threatens irreparable harm to national security and the public interest by injecting added burdens and dangerous confusion into the conduct of military operations abroad during an active armed conflict.”

On Monday — on the 225th anniversary of the signing of the final draft of the US Constitution — Judge Raymond Lohier of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals temporarily stayed Judge Forrest’s injunction, in a brief, one-page ruling, a move that, as the New American noted, “effectively repealed many of that document’s fundamental protections of individual liberties.”

So why the urgency? As Chris Hedges asked on Monday, “If the administration is this anxious to restore this section of the NDAA, is it because the Obama government has already used it? Or does it have plans to use the section in the immediate future?”

A plausible explanation was provided by one of the lawyers in the case, co-lead counsel Bruce Arfan, who stated, “A Department of Homeland Security bulletin was issued Friday claiming that the riots [in the Middle East] are likely to come to the US and saying that DHS is looking for the Islamic leaders of these likely riots. It is my view that this is why the government wants to reopen the NDAA — so it has a tool to round up would-be Islamic protesters before they can launch any protest, violent or otherwise. Right now there are no legal tools to arrest would-be protesters. The NDAA would give the government such power. Since the request to vacate the injunction only comes about on the day of the riots, and following the DHS bulletin, it seems to me that the two are connected. The government wants to reopen the NDAA injunction so that they can use it to block protests.”

Bruce Arfan may be right, and it may be that the current unrest — blamed on an anti-Islamic film, but more honestly to do with the ongoing injustice of US foreign policy, and Obama’s extensive use of drones — has shaken the administration to such an extent that they fear reprisals in the US, and want to be prepared.

That does not explain why the administration has been fighting Judge Forrest for many months, although it does explain why reports from the plaintiffs suggest a recent spike in the level of the government’s hysteria. Unfortunately for the administration, though, the detention policies at Guantánamo that these provisions echo have, from the beginning, been a dangerous aberration. The Geneva Conventions and US criminal statutes still provide all the tools necessary to detain people regarded as dangerous.

If the administration has other views regarding military detention without charge or trial — such as finding an excuse to hold people indefinitely on suspicion of what they might do — senior officials need to stop before they start down this road. Men are dying at Guantánamo after ten years against whom no actual evidence of wrongdoing exists, and this and all the other ruinous lawlessness that was implemented by the Bush administration does not, in the end, make Americans safer. Obama once claimed to know that the kind of injustices enshrined at Guantánamo only serve to recruits enemies for America. Revisiting those injustices through the NDAA — if that is what the administration has in mind — is not the answer, and should be avoided at all costs.

Andy Worthington is the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison.

by

by