Last week, at a meeting of the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva, Professor Juan Méndez, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, spoke about the case of Pfc. Bradley Manning, the alleged WikiLeaks whistleblower, telling the news agency AFP, “I believe Bradley Manning was subjected to cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment in the excessive and prolonged isolation he was put in during the eight months he was in Quantico.”

This was a reference to the US military brig near Washington D.C., where Manning was held after his arrest in Kuwait, and before he was moved to Fort Leavenworth in Kansas (on April 20 last year). when his treatment noticeably improved. I wrote about Manning’s ill-treatment at the time, in my articles, Is Bradley Manning Being Held as Some Sort of “Enemy Combatant”?, Psychologists Protest the Torture of Bradley Manning to the Pentagon; Jeff Kaye Reports, and Former Quantico Commander Objects to Treatment of Bradley Manning, the Alleged WikiLeaks Whistleblower. In addition, as I noted in an article last November, after Manning had been charged, and when a date was set for his first hearing:

Among the disturbing details to emerge was information about his chronic isolation, and about the enforced use of nudity to humiliate him, all of which provided uncomfortable echoes of the Bush administration’s torture program, as used in military brigs on the US mainland on two US citizens, Jose Padilla (who lost his mind as the result of his torture) and Yaser Hamdi, and US resident Ali al-Marri.

As AFP also noted last week, “Professor Méndez said that ‘fortunately’ the alleged mistreatment ended when Manning was transferred from Quantico” to Fort Leavensworth, but he added that “the explanation I was given for those eight months was not convincing for me.”

Professor Méndez’s comments came just eleven days after Manning’s arraignment hearing at Fort Meade, on February 23, when he declined to enter a plea in response to the 22 charges — including “aiding the enemy,” which potentially carries a death sentence — that he is facing for his alleged involvement in the release of classified military documents.

These include the “Collateral Murder” video, showing US soldiers killing civilians in Iraq in 2007, hundreds of thousands of pages of war logs from Afghanistan and Iraq, over 250,000 diplomatic cables, whose selective release, beginning in December 2010, drove the news agenda globally for many weeks (and also see my reflections on what they revealed about Guantánamo and US torture), and the military files on the Guantánamo prisoners, released last April, on which I worked with WikiLeaks as a media partner, and have since been analyzing in a major, 70-part series, “The Complete Guantánamo Files.”

Now Professor Méndez’s criticism of the US government’s actions in Bradley Manning’s case has been made publicly available as part of an Addendum to the “Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment,” at the 19th session of the Human Rights Council, comprising “Observations on communications transmitted to Governments and replies received.” In the report (PDF, pp. 74-5), Professor Méndez wrote:

UA 30/12/2010 Case No. USA 20/2010 State reply: 27/01/2011 19/05/2011 Allegations of prolonged solitary confinement of a soldier charged with the unauthorized disclosure of classified information.

170. The Special Rapporteur thanks the Government of the United States of America for its response to this communication regarding the alleged prolonged solitary confinement of Mr. Bradley E. Manning, a US soldier charged with the unauthorized disclosure of classified information. According to the information received, Mr. Manning was held in solitary confinement for twenty-three hours a day following his arrest in May 2010 in Iraq, and continuing through his transfer to the brig at Marine Corps Base Quantico.

His solitary confinement — lasting about eleven months — was terminated upon his transfer from Quantico to the Joint Regional Correctional Facility at Fort Leavenworth on 20 April 2011. In his report, the Special Rapporteur stressed that “solitary confinement is a harsh measure which may cause serious psychological and physiological adverse effects on individuals regardless of their specific conditions.” Moreover, “[d]epending on the specific reason for its application, conditions, length, effects and other circumstances, solitary confinement can amount to a breach of article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and to an act defined in article 1 or article 16 of the Convention against Torture.” (A/66/268 paras. 79 and 80)

Before the transfer of Pfc Manning to Fort Leavenworth, the Special Rapporteur requested an opportunity to interview him in order to ascertain the precise conditions of his detention. The US Government authorized the visit but ascertained that it could not ensure that the conversation would not be monitored. Since a non-private conversation with an inmate would violate the terms of reference applied universally in fact-finding by Special Procedures, the Special Rapporteur had to decline the invitation. In response to the Special Rapporteur’s request for the reason to hold an unindicted detainee in solitary confinement, the government responded that his regimen was not “solitary confinement” but “prevention of harm watch” but did not offer details about what harm was being prevented. To the Special Rapporteur’s request for information on the authority to impose and the purpose of the isolation regime, the government responded that the prison rules authorized the brig commander to impose it on account of the seriousness of the offense for which he would eventually be charged.

The Special Rapporteur concludes that imposing seriously punitive conditions of detention on someone who has not been found guilty of any crime is a violation of his right to physical and psychological integrity as well as of his presumption of innocence. The Special Rapporteur again renews his request for a private and unmonitored meeting with Mr. Manning to assess his conditions of detention.

Professor Méndez’s references to the UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the UN Convention Against Torture cannot be easily dismissed by the Obama administration.

When he mentioned that “solitary confinement can amount to a breach of article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,” for example, he was referring to a passage that guarantees that “No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.” Furthermore, his reference to “an act defined in article 1 or article 16 of the Convention against Torture” refers to the following:

- In Article 1, the explanation that “‘torture’ means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.”

- In addition, there is the following requirement in Article 16: “Each State Party shall undertake to prevent in any territory under its jurisdiction other acts of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment which do not amount to torture as defined in article 1, when such acts are committed by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.”

Speaking to the Guardian after a 14-month investigation that began around the time that I shared a panel with him at an event marking the 9th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, at the university in Washington D.C. where he teaches, Professor Méndez largely reiterated what he told AFP a week ago in Geneva. Speaking of the three months Bradley Manning was imprisoned in Camp Arifjan in Kuwait, followed by his eight months in Quantico, he said, “I conclude that the 11 months under conditions of solitary confinement (regardless of the name given to his regime by the prison authorities) constitutes at a minimum cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment in violation of article 16 of the convention against torture. If the effects in regards to pain and suffering inflicted on Manning were more severe, they could constitute torture.”

The Guardian also included the documents mentioned in the UN report — Professor Méndez’s first letter to the US government on December 30, 2010 (PDF), in which he suggested that a program of prolonged isolation had been imposed “in an effort to coerce him into ‘cooperation’ with the authorities, allegedly for the purpose of persuading him to implicate others” — in other words, Julian Assange of WikiLeaks, against whom “the Department of Justice is conducting a grand jury in Virginia exploring the possibility of bringing charges” — and two US responses.

In the first, dated January 27 2011 (PDF), the US Mission to the UN in Geneva stated that the US government “is committed to protecting human rights in our country and abroad, and we value the work of the special rapporteur,” which essentially means nothing, and in the second letter, dated May 19, 2011 (PDF), the Pentagon’s General Counsel, Jeh Johnson, stated that there was “considerable misinformation” about Manning’s treatment in Quantico, which “was in compliance with legal and regulatory standards in all respects.” Johnson also wrote, “Though Private Manning was classified as a maximum custody detainee at Quantico, he occupied the very same type of single-occupancy cell that all other pretrial detainees occupied.”

As the Guardian also explained, “the Pentagon’s arguments did not impress the special rapporteur,” who not only delivered the verdict published in his report, but also “said that the US government had tried to justify Manning’s solitary confinement by calling it ‘prevention of harm watch,’” even though “the military had offered no details as to what actual harm was being prevented.”

He also told the Guardian that “he could not reach a definitive conclusion on whether Manning had been tortured,” because he had “consistently been denied permission by the US military to interview the prisoner under acceptable circumstances.” As the Pentagon explained, “You should have no expectation of privacy in your communications with Private Manning,” prompting Professor Méndez to respond that the “lack of privacy is a violation of human rights procedures,” and “considered unacceptable by the UN special rapporteur.”

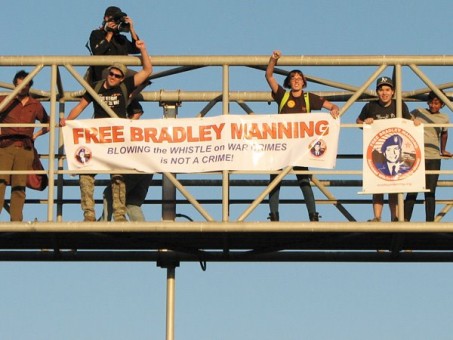

It remains to be seen whether Professor Méndez’s verdict will play a part in Bradley Manning’s forthcoming trial, but it will surely add moral weight to the arguments of those who regard Bradley Manning as a hero, and a victim of US torture, and not as a criminal responsible for “aiding the enemy.”

Andy Worthington is the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison.