Last week, Guantánamo briefly resurfaced in the news when one of the remaining 171 prisoners, Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, was arraigned for his planned trial by Military Commission, for his alleged role in the bombing of the USS Cole in 2000.

Al-Nashiri’s trial will not begin for a least a year, and his fleeting appearance was not sufficient to keep attention focused on Guantánamo, especially as the 24-hour news cycle — and people’s addiction to it — now barely allows stories to survive for a day before they are swept aside for the latest breaking news.

As a result, the opportunity to ask bigger questions, such as, “Who is still at Guantánamo?” and “Why are they still held?” was largely missed. These are topics I have been discussing all year, but they are rarely mentioned in the mainstream media, so it was refreshing, last week, to see Peter Finn in the Washington Post address these questions.

In “Guantánamo detainees cleared for release but left in limbo,” Finn, with assistance from Julie Tate, began by revisiting the final report of the Guantánamo Review Task Force, the 60 or so officials and lawyers from government departments and the intelligence agencies who reviewed the cases of all the prisoners throughout 2009, and who, as Finn noted, cleared 126 prisoners for transfer out of Guantánamo (PDF) — and also recommended 36 for trials, and 48 for indefinite detention without charge or trial.

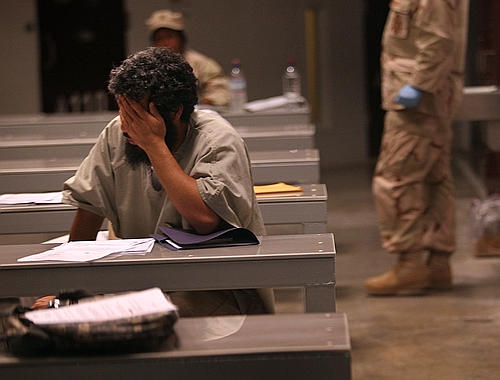

Finn did a good job of examining what has happened to these 126 prisoners, and how, after a promising start, in which, “[a]s they began flying off, to either their home nations or others for resettlement, a sense of optimism pulsed through the camps,” the releases “have ground to a halt because of congressional restrictions and decisions by President Obama that have left dozens of detainees in limbo,” so that now, as Cori Crider, the legal director of the legal action charity Reprieve, whose lawyers represent dozens of the remaining prisoners, explained, “It’s beyond frustrating. There’s a kind of hopelessness and cruelty.”

Even in the early, hopeful phase of Obama’s Presidency, there were warning signs that closing Guantánamo would require more vigor than was displayed by the President. Despite issuing an executive order, on his second day in office, promising to close the prison within a year, only one prisoner was freed in the next four months. Obama’s Task Force struggled to comprehend who Obama had inherited from George W. Bush, and a straightforward course of action — releasing 66 men cleared for release by military review boards under President Bush, who were still held — was not taken by the President.

Eventually, as Finn noted, 67 prisoners were released by Obama, “with 27 going home; 38 resettling in third countries, mostly in Europe; and two being sent to Italy for prosecution.” However, as he also explained, “The administration on its own authority has not been able to transfer any detainees since September 2010, when a Palestinian and a Syrian were sent to Germany.” One more living prisoner has left since that time — an Algerian, Farhi Saeed bin Mohammed, who won his habeas corpus petition, and was repatriated in January this year — but since then the only way out of Guantánamo has been by dying. Two Afghan prisoners (Awal Gul and Hajji Nassim, known to the US authorities as Inayatullah) died at the prison this year, but the Post‘s editors chose not to mention this.

In explaining how the release of prisoners has ground to a halt, Peter Finn correctly identified that a major obstacle was “the attempted bombing of a commercial airliner by a Nigerian man with a bomb in his underwear” on Christmas Day 2009. The capture of that man, Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, who “pleaded guilty to terrorism charges in Detroit last month,” and was “recruited and trained by al-Qaeda’s affiliate in Yemen, where the bomb was built,” sparked an uproar in mainly Republican circles in the US.

In response, even though the attack failed, and there was no known connection between any of the Yemenis in Guantánamo and the al-Qaeda cell in their home country, the Obama administration, as Finn put it, “suspended the transfer home of any more of the 29 Yemenis who had been cleared for repatriation,” following the release of seven Yemenis just before the foiled attack took place.

Finn explained that, although this affected the Yemenis, prisoners from other countries “continued to leave Guantánamo, until Congress passed restrictions as part of the 2011 National Defense Authorization Act.” As he put it, “One critical provision demanded that the defense secretary certify that he would ‘ensure’ that a freed ‘individual cannot engage or re-engage in any terrorist activity,’” which, as Jeh Johnson, the Defense Department’s general counsel, explained in a speech last month at the Heritage Foundation, was a provision that was “onerous and near impossible to satisfy.”

The provision had been inserted because of lawmakers’ fearful response to a series of unsubstantiated announcements, emanating from the Pentagon, indicating that there were mounting problems with the recidivism of released prisoners. At various points from May 2009 onwards, the Pentagon, or other agencies, claimed that 1 in 7, 1 in 5 and 1 in 4 of the released prisoners were engaged in anti-US activities, but never provided the evidence to back up their claims.

I examined the allegations, which can only objectively be viewed as propaganda, in a number of articles, including New York Times finally apologizes for false Guantánamo recidivism story, Guantánamo Recidivism: Mainstream Media Parrot Pentagon Propaganda (Again) and Countering Pentagon Propaganda About Prisoners Released from Guantánamo, and I’m pleased to note that, in dealing with the claims, the Post refused to uncritically parrot the official line. Instead, Peter Finn noted, “The degree of recidivism among Guantánamo detainees remains a matter of dispute, and the Pentagon has not released the names of those who it alleges have returned to the fight.”

As Finn noted, however, whatever the origins of the provision approved by Congress, the result is that it has “stranded most of the 32 detainees [I make it 31] who were on track to be transferred when Congress acted.” He added that the administration “refuses to release to the public the names of those cleared for transfer, even though the detainees themselves, and in many cases their families, have been told of their status,” but noted that it is, at least, known that this group includes the five remaining Uighurs (Muslims from China’s oppressed Xinjiang province) out of the 17 who were “ordered released by the courts” in October 2008, after winning their habeas corpus petitions. Rather breezily, the article notes that “the administration has not been able to find a country where they want to go,” which does not quite do justice to the ways in which the Uighurs have persistently been failed by the administration, Congress and the judiciary, despite being palpably innocent of any wrongdoing. For a heart-breaking analysis of that, I recommend reading The Abandonment of Guantánamo’s Uighurs and Attorney Sabin Willett’s Powerful Requiem for Habeas Corpus in the US.

In the most significant section of the Washington Post article, Peter Finn noted that lawyers for the prisoners “insist that the administration still has options to continue its stated policy of reducing the population at Guantánamo Bay and, ultimately, closing the facility,” noting, crucially, “The congressional restrictions do not bar the administration from transferring someone who has been ordered released by a federal court,” and explaining that, in July 2010, the administration “lifted its ban on returning Yemenis home to repatriate one man [Mohammed Hassan Odaini] after a court ruled that there was ‘overwhelming’ evidence that he had been wrongfully detained.”

This route to releasing prisoners was specifically mentioned by J. Wells Dixon, a senior staff lawyer at the Center for Constitutional Rights, which represents a number of Guantánamo prisoners, who pointed out that the government “could stop contesting the habeas corpus petitions of those detainees it wants to transfer,” and, “without admitting error,” could, in conjunction with prisoners’ lawyers, “ask the court to enter an order disposing of the case and directing the release” of a prisoner it no longer wishes to hold.

This would indeed be sensible, but, as I have repeatedly noted, the administration has shown no willingness to insist that the findings of the Task Force be taken on board by the Justice Department lawyers trying to make sure that all the prisoners, whether approved for transfer or not, lose their habeas petitions. As I have also noted, after initially honouring court rulings, the administration has increasingly opted instead to appeal successful habeas petitions, especially, it seems, in the cases of Yemeni prisoners, which appears to have been become a matter of policy for nakedly political reasons.

Moving on to another route whereby prisoners could leave Guantánamo, Dixon also pointed out that the administration “could seek plea agreements in military commissions.” The Post noted that defense secretary Leon Panetta is “expected to certify” that Omar Khadr, the Canadian citizen and former child prisoner, who reached a plea deal a year ago, “can be repatriated” to serve the last seven years of an eight-year sentence in Canada. Other cases were not mentioned, but two other trials were decided by plea deal — that of Ibrahim al-Qosi, a cook, who should be repatriated to Sudan in July 2012 after negotiating a two-year sentence in July 2010, and Noor Uthman Muhammed, a military trainer, who should be repatriated to Sudan in December 2013 after negotiating a 34-month sentence in February this year.

As Dixon explained, prisoners “‘would line up’ to make similar plea deals if there were a chance to get out of Guantánamo.”

Despite the fact that there is something monstrously wrong when the only way out of a prison is through a plea deal, and insignificant prisoners are wishing they were regarded as more significant than they are so that they might have a chance of being charged and thereby negotiating a plea deal, a government official also told the Post that cowardice and indifference remained official policy regarding Guantánamo.

He didn’t use those words, of course, even though the effect was the same. Instead, the anonymous spokesperson said that the administration “will not try to defy Congress by attempting to circumvent the restrictions — at least not yet.” The source explained, “It’s the kind of sleight of hand that in the current political climate could get you in a lot of trouble. At the moment, it’s better to be straight than be clever. The legislation is not fixed, and you can imagine the process picking up again.”

In conclusion, then, there still appears to be no light at the end of the tunnel for any of the men awaiting release from Guantánamo, although Finn noted that the current restrictions expire at the end of the year, and that “[s]enior Democrats on the Senate’s Intelligence and Judiciary committees have expressed concern about renewed Guantánamo restrictions, even though they came out of the Armed Services Committee with bipartisan support.”

He also noted that the restrictions are included in the new National Defense Authorization Act (which is attracting notoriety for seeking mandatory military detention for terror suspects), where there has been some resistance from Democrats and the administration, although a sign that President Obama is no closer than ever to ending his paralysis regarding making a stand on Guantánamo must surely be that the most prominent critic of Congressional interference with the President’s right to deal with prisoners as he sees fit is Charles “Cully” Stimson, formerly the deputy assistant defense secretary for detainee affairs in the Bush administration.

In a memo published last month by the Heritage Foundation, Stimson asked, “Does the proposed legislation support and respect the President’s executive power under the Constitution to prosecute the war as he sees fit, or does it impose inflexible and unnecessary restrictions on him?” In response to his own question, he said that the President should be able to decide on the “detention, release, transfer, review, and forum for prosecution of the enemy.” Stimson’s memo was no liberal critique of Guantánamo, and it contains its own problems, but the fact that he is defending the President, and the President himself is not doing so, ought to tell us something about the extent to which Barack Obama has given up on Guantánamo.

Andy Worthington is the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison.