Carrying signs that read, “Execute Justice not People,” and hoisting a large peace sign embellished with yellow, pink, and white flowers, about 40 people gathered Friday at Frank Ogawa Plaza in downtown Oakland to protest the execution of Troy Davis in Georgia.

Davis, who was put to death Thursday night after more than a decade of controversy over his case, was convicted of the murder of an off duty police officer, Mark MacPhail, on August 19th, 1989 in Savannah, Georgia. He was sentenced to death two years later. Objections over the case’s resolution emerged as seven out of the nine eyewitnesses recanted their testimonies, and Davis’ impending execution gained national and international attention from organizations such as Amnesty International, and the NAACP. World leaders, including Desmond Tutu, urged the court to review his case, and it was reported that “Pope Benedict XVI’s US envoy sent a letter pleading for his life.” Former US President Jimmy Carter, called the decision “unjust and outdated” and urged Georgia’s Board of Pardons and Parole to review Davis’ conviction. Global protests commenced in the streets and online, where Twitter users exchanged messages under the hash tag “Too much doubt.” The board ultimately denied Davis clemency and he was put to death by lethal injection at 11:08 pm on Thursday.

“I’m outraged,” said protester Martha Hubert, a member of the organization Code Pink: Women for Peace, who came to Friday’s rally straight from another protest. “You’re innocent until proven guilty, not the other way around.”

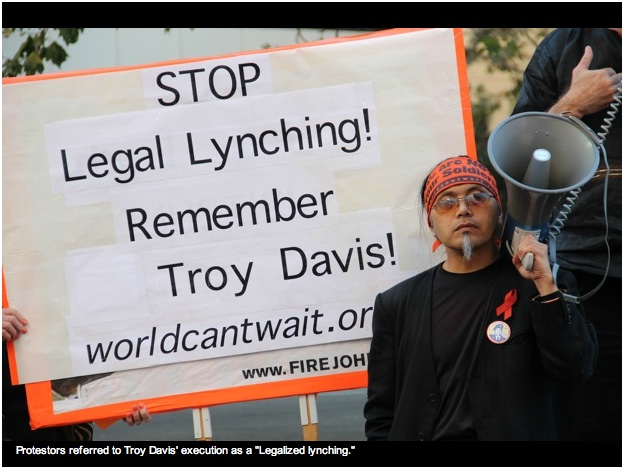

Recounting the murder of Oscar Grant by BART police in 2009, protestors at Ogawa Plaza said Davis’ execution was another reflection of the disparities people of color face in criminal and court procedure. “Troy Davis is emblematic of the entire criminal justice system,” said Stephanie Tang, a member of the San Francisco chapter of the organization The World Can’t Wait and one of the lead organizers of the protest. Holding out an orange flier with the words “Legally Lynched in the USA” typed out in bold letters under a picture of Davis, Tang wiped at the corner of her eyes. “The prison system today is part of a new system of Jim Crow laws,” she said.

The rally was a culmination of poetry recitations (“White Day in AmeriKKKa”), freedom songs, unified chanting of “I am Troy Davis,” signing heart-shaped condolence letters which would be sent to Davis’ family, and an opportunity for people in the crowd to share their thoughts over the megaphone. New York native and Oakland resident, Michlene Cotter-Norwood, came to the rally with her two young daughters and teenage son. “Georgia broke our heart,” she told the crowd. “Obama broke my heart.”

Davis was not the only American convict executed on Thursday. On the same night, Lawrence Russell Brewer was put to death in Texas for a hate crime against James Byrd Jr. in 1998. Brewer was white, and Byrd was black. When asked about Brewer’s execution, which received minimal media attention from anti-death penalty activists, protestors agreed that it was also wrong. “What happened in Texas was an awful crime,” said Cotter-Norwood. “But in its truest sense, that is what prison for.”

Standing solemnly during rush hour on Friday against the backdrop of 14th Street and Broadway, Hubert held a large pink banner that read, “Shame! Troy Davis Executed – No More Death Penalty.” The same sentiment applied to the Brewer case, she said. Brewer “needed help,” Hubert said. ”He didn’t need to be killed. He needed psychiatric care, sensitivity training, and to get to know someone with the color of skin he was against.”

Protestors argued that the death penalty neither deters crime nor brings healing to victims’ families. “How does unjustly killing one person somehow heal another unjust killing?” Tang asked. Oakland resident and firm anti-death penalty proponent, Bob Heaney, said he does not believe the death penalty can do that. “I’ve had crime in my family – my cousin was killed in LA,” he said. “But it doesn’t do anything for the family.”

MacPhail’s mother, Anneliese MacPhail, told reporters on the Saturday before Davis’ execution, “I will never have closure, but I may have some peace when he is executed.” But Cotter-Norwood said she didn’t see how MacPhail’s family would get that sense of peace. “As a mother, I know nothing would bring me peace, except to have my child back,” she said, as she wrapped her arm around her youngest daughter.

Several protestors believed that the death penalty could be replaced with better, and more equal, socio-economic conditions. “We need to address questions of poverty and provide a civilized country where everyone has the right to a job,” said Heaney. “That’ll do more to solve the issue of crime.” Justin Childs, who recently moved to Oakland from Bakersfield, echoed Heaney’s sentiments about the relationship between the lack of jobs and crime. “When you back someone into a corner like a dog, they bite,” he said. “People have to survive.”

As the afternoon sun began its descent, about a dozen people remained after the rally to march down Broadway. Some passing cars honked in solidarity as protestors shouted, “Remember Troy Davis! No more death penalty!” and urged AC Transit passengers to “Get off the bus!” and join them.

After rounding 9th Street and Broadway, protestors headed back to the Plaza. Standing linked together hand in hand in a circle, protestors observed a moment of silence for Davis, before wrapping up their banners and drums and heading home.

“My hope is we’ll end the death penalty,” said Hubert, her face weary from a long day of protesting. “And give people opportunities instead of locking them up.”

This article originally appeared in Oakland North on September 24, 2011.

by

by