By Andy Worthington

A major new report on secret detention policies around the world, conducted by four independent UN human rights experts, concludes that, "On a global scale, secret detention in connection with counter-terrorist policies remains a serious problem," and, "If resorted to in a widespread and systematic manner, secret detention might reach the threshold of a crime against humanity."

The 226-page report, published on Wednesday in an advance unedited version, is the culmination of a year-long joint study by the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism, the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention and the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances. It will be presented to the UN Human Rights Council in March.

In an introduction, the UN experts established that: “a person is kept in secret detention if State authorities acting in their official capacity, or persons acting under the orders thereof, with the authorization, consent, support or acquiescence of the State, or in any other situation where the action or omission of the detaining person is attributable to the State, deprive persons of their liberty; where the person is not permitted any contact with the outside world ("incommunicado detention"); and when the detaining or otherwise competent authority denies, refuses to confirm or deny or actively conceals the fact that the person is deprived of his/her liberty, hidden from the outside world, including, for example, family, independent lawyers or non-governmental organizations, or refuses to provide or actively conceals information about the fate or whereabouts of the detainee.”

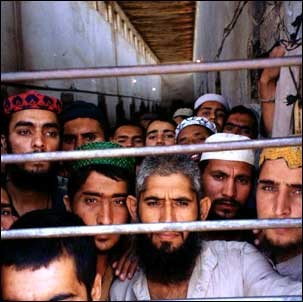

After running through the historical background to secret detention – both in a legal context, and through numerous examples from the 20th century – the report focused primarily on secret detention in the last nine years, providing a detailed account of US policies in the wake of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and also running through the practice of secret detention in 25 other countries, including Algeria, China, Egypt, India, Iraq, Iran, Israel, Libya, Pakistan, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Syria, Uganda and Zimbabwe.

These sections contain valuable summaries, explaining how, in many cases, terrorism is used as a cover for secret detention policies of a political nature. However, the heart of the report is a detailed analysis of the Bush administration’s "war on terror" policies.

Of particular concern to the authors of the joint study – beyond the overall illegality of the entire project conceived and executed by the Bush administration – is the fate of dozens of men held in secret prisons run by the CIA, or transferred by the CIA to prisons in other countries. Based on figures disclosed in one of the Office of Legal Counsel’s notorious "torture memos," written in May 2005 by Assistant Attorney General Stephen Bradbury, the CIA had, by May 2005, "taken custody of 94 prisoners [redacted] and ha[d] employed enhanced techniques to varying degrees in the interrogations of 28 of these detainees."

The 28 men subjected to "enhanced techniques" are clearly the "high-value detainees" – including Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged mastermind of the 9/11 attacks, and Abu Zubaydah – who were transferred to Guantánamo in September 2006, but no official account has ever explained what happened to the other 14 high-value detainees, or, indeed, to the majority of the other 66 men.

The report also established that, at a minimum, many dozens of other prisoners were rendered to prisons in other countries.

In tracking these men, the report traced the development of the US secret detention program, drawing on new research into flight records to demonstrate that rendition flights, carefully disguised in the records, flew to Poland, Romania and Lithuania. The report also touched on the existence of a secret facility within Guantánamo, exposed by Scott Horton for Harper’s Magazine last week, which prompted the experts to note that they were "very concerned about the possibility that three Guantánamo detainees (Salah Ahmed Al-Salami, Mani Shaman Al-Utaybi and Yasser Talal Al-Zahrani) might have died during interrogations at this facility, instead of in their own cells, on 9 June 2006."

Also mentioned are two little-reported facilities in the Balkans – Camp Bondsteel in Kosovo and Eagle Base in Tuzla, Bosnia-Herzegovina – and a claim that Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean (a British territory leased to the US) was used in 2005-06 to hold Mustafa Setmariam Nasar, a joint Syrian-Spanish national.

Accounting for other prisoners, the report focused on a number of secret prisons in Afghanistan – in particular, the "Dark Prison," the "Salt Pit" and a secret facility within Bagram airbase. Of the 94 men mentioned by Stephen Bradbury – minus the 14 transferred to Guantánamo in September 2006 – the report established that eight were released, that 23 others were transferred to Guantánamo (mostly in 2004), that four escaped from Bagram in July 2005, that four others are still in Bagram (three of whom are awaiting a US appeals court ruling on their successful habeas corpus petition last March) and that five others were returned to Libya in 2006.

These five include Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi, the CIA’s most notorious "ghost prisoner," who falsely confessed, under torture in Egypt, that there were connections between al-Qaeda and Saddam Hussein, which were subsequently used to justify the invasion of Iraq. After multiple renditions to other countries, al-Libi’s return to Libya came to a dark end last May, when he died under mysterious circumstances.

Discussing the other prisoners, whose current whereabouts are unexplained, the experts noted, "It is probable that some of these men have been returned to their home countries, and that others are still held in Bagram." As I explained in an article last week, following the publication of the first ever list of prisoners held in Bagram, it appears that a handful of these men may indeed be in Bagram, but not all of them, and it is, therefore, imperative that the publication of this list leads to pressure on the Obama administration to reveal details of all the "disappeared" detainees.

The report also examined the cases of 35 men rendered by the CIA to Jordan, Egypt, Syria and Morocco, between 2001 and 2004. As with the "ghost prisoners" in Afghanistan, many of these men later surfaced in Guantánamo, or were freed, but the whereabouts of others – particularly those in Syria, and, probably, other completely unknown men rendered to Egypt – are unknown, even though some of the prisoners rendered to Syria were flown there as long ago as 2002, and, in at least two cases, were only teenagers at the time.

There are also sections on secret detention in Ethiopia, Djibouti and Uzbekistan, and the experts also criticized other countries for their involvement in the program, including Australia, Canada, Germany, Italy, Kenya and the UK. According to Reuters, throughout the report, 66 countries in total are implicated in one way or another in secret detention practices – either independently, or as part of the US-led war on terror.

In concluding their review of US detention policies since 9/11, the experts welcomed President Obama’s commitment to revoke and repudiate many of the Bush administration’s policies, including the closure of all CIA black sites, but requested clarification "as to whether detainees were held in CIA ‘black sites’ in Iraq and Afghanistan or elsewhere when President Obama took office, and, if so, what happened to the detainees who were held at that time." They were also "concerned that the Executive Order which instructed the CIA ‘to close any detention facilities that it currently operates’ does not extend to the facilities where the CIA detains individuals on ‘a short-term transitory basis,’" and, in the light of suggestions by Scott Horton that the secret facility at Guantánamo may have been run by the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), noted that the order "does not seem to extend to detention facilities operated by" JSOC.

These were not their only concerns. Although they welcomed the implementation in August 2009 of a new policy whereby the International Committee of the Red Cross must be notified of all prisoners’ names within two weeks of capture, they noted that "there is no legal justification for this two-week period of secret detention," because the Geneva Conventions allow only a week, and also because of their fears that some prisoners are being held who were not captured on the battlefield, and who may, as I noted in an article in September, in fact be prisoners who have been rendered to facilities outside of the military’s control (at Bagram in Afghanistan and Camp Nama in Iraq). The experts explained that they had "noted with concern news reports which quoted current government officials saying that ‘the importance of Bagram as a holding site for terrorism suspects captured outside Afghanistan and Iraq has risen under the Obama administration, which barred the Central Intelligence Agency from using its secret prisons for long-term detention.’"

The experts’ final concern was with Bagram’s new review system for prisoners. They noted that the decision to replace the existing system, which the judge in the habeas cases last March described as a process that "falls well short of what the Supreme Court found inadequate at Guantanamo," was still inadequate. As they explained:

[T]he new review system fails to address the fact that detainees in an active war zone should be held according to the Geneva Conventions, screened close to the time and place of capture if there is any doubt about their status, and not be subjected to reviews at some point after their capture to determine whether they should continue to be held.

They were also "concerned that the system appears to specifically aim to prevent US courts from having access to foreign detainees captured in other countries and rendered to Bagram," and, despite welcoming the release of the names of 645 prisoners at Bagram, urged the US government "to provide information on the citizenship, length of detention and place of capture of all detainees currently held within Bagram Air Base."

While the report spreads its net wide, the US administration’s response to its findings about the Bush administration’s legacy of "disappeared" prisoners, and its focus on the gray areas of Obama’s current policies, is particularly anticipated. So far, however, there has been silence from US officials, and only the British, moaning about "unsubstantiated and irresponsible" claims, have so far dared to challenge their well-chronicled complicity in the secret detention policies underpinning the whole of the war on terror, which do not appear to have been thoroughly banished, one year after Barack Obama took office.

This article originally appeared on Truthout.