By Colonel (Ret) Ann Wright | originally posted on codepink.org

On January 11, 2026, thousands of citizens of various countries held vigils for the 15 men still being held in the U.S. military prison at the U.S. Naval Base in Guantánamo, Cuba. As these citizens have done for over two decades, from London to Washington, DC to Honolulu, they are the voices of conscience for one of the most brutal episodes in U.S. history,: the torture and imprisonment of hundreds of men who had nothing to do with the events of September 11, 2001.

Twenty-four years ago, 8760 days ago.

On January 11, 2002, the first twenty detainees from Afghanistan arrived by military aircraft at the U.S. Naval Base in Guantánamo, Cuba.

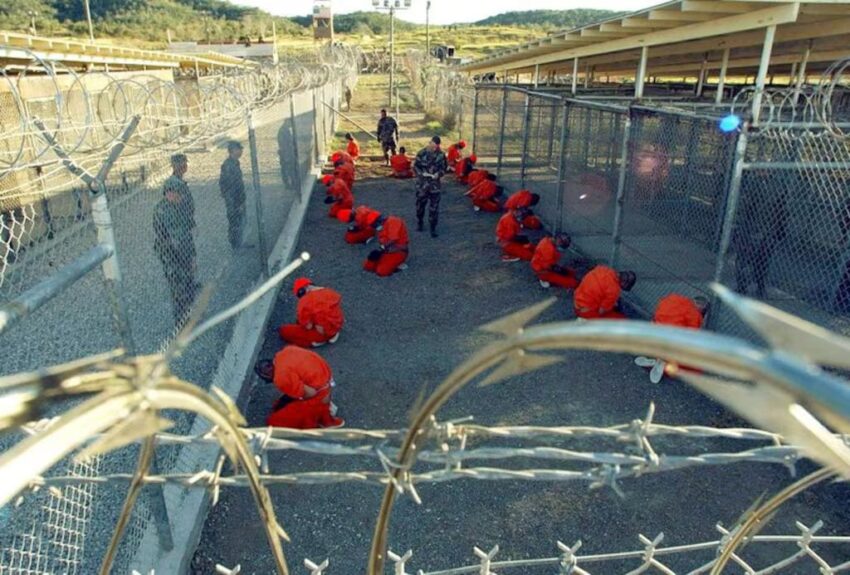

In Guantánamo, they were initially kept in a place called Camp X-Ray, in cages in the open air, with snakes and rodents free to enter.

Over the next months and years, a total of 780 detainees from 48 countries were brought to the prison from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and “dark sites” in many countries that signed on to help extract information from detainees through torture overseen by the CIA.

Of the 780 detainees, 86% were purchased by the CIA and U.S. military from neighbors or others with a grudge.

The flight of the first 20 prisoners to Guantánamo was a classified, “need to know” CIA/military operation

On January 11, 2002, I was working at the recently reopened U.S. Embassy in Kabul, an embassy that had been closed for 12 years.

The CIA operation in Afghanistan had been running since October 2001. The CIA had built up its own air transport service, hotel, and fleet of ground vehicles.

The tiny U.S. Embassy had five Foreign Service employees who arrived in mid-December and lived in a bunker on the Embassy grounds. A contingent of U.S. Marines provided security services and lived on top of the Embassy and inside a few rooms in the Embassy.

U.S. Army Special Forces teams were riding horses with one of the friendly warlords, brutal General Dostum, who was later the vice president of the country. Bagram Air Base was controlled by the U.S. military. The international airport in Kabul was closed as the U.S. had bombed the runways.

To my knowledge, the Bush administration’s Special Envoy to Afghanistan, Zalmay Khalilzad, was the only person associated with the Embassy in Kabul who knew about the classified, “need to know” transfer of detainees from U.S. detention facilities in Afghanistan to the new prison in Guantánamo, Cuba.

Certainly, State Department officials in Washington had to sign off on the Department of Defense’s recommendation to transfer detainees to Cuba, outside the reach of the U.S. civilian judicial system, but the decision on the timing of flying detainees to Cuba was so sensitive that those of us at the Embassy did not know of it.

780 detainees have been in Guantánamo prison in the past 24 years

780 prisoners have been held by the U.S. military at Guantánamo since the prison opened on January 11, 2002. Of those, 755 have been released or transferred, including one who was transferred to the U.S. to be tried and subsequently convicted. A timeline of the history of Guantánamo prison is here.

More than 500 detainees were transferred out of Guantánamo during the George W. Bush administration. President Barack Obama brought the number down to 41, and only one detainee was transferred during the first Trump administration. During the Biden administration, 25 detainees were transferred out of the facility. None have been transferred in the second Trump administration.

Nine prisoners died while in the U.S. Guantánamo prison, the last of these being Adnan Latif, in September 2012.

Fifteen prisoners remain in Guantánamo prison

15 men are still held in the prison.

Three Guantánamo inmates—a Libyan, a Somalian, and a stateless Rohingya—were approved for transfer years ago but remain imprisoned. The Libyan and Somalian detainees cannot be returned to their homelands because those countries, like Yemen, are on Congress’s no-transfer list due to security concerns—so the U.S. must find other countries in which to resettle them.

Three other prisoners have been described as “forever prisoners,” held without charge or trial, and with their cases only reviewed via an administrative, rather than a legal process—the Periodic Review Boards established under President Obama.

Nine others are facing or have already faced trials in the military commission system.

Six have active cases in the military commission system.

One is serving a life sentence, largely in solitary confinement, after a one-sided trial in 2008 in which he refused to mount a defense.

Another prisoner agreed to a plea deal in 2022,

The last of the nine is in legal limbo, after a DoD Sanity Board ruled that he was unfit to stand trial in 2023.

The profiles of the 15 who remain imprisoned at Guantánamo are here.

The Biden administration transferred 15 from Guantánamo in the last weeks of the administration

On January 6, 2025, just two weeks before leaving office, President Biden authorized the transfer of 11 Yemeni detainees to Oman, which agreed to help resettle them and provide security monitoring. Oman has accepted at least 30 other Guantánamo prisoners in the past.

The transfer of the 11 Yemenis, which had been scheduled for October 2023, had been on hold for over two years due to the Biden administration’s weapons support to the Israeli military’s bombing and destruction of Gaza and the resulting instability in the region.

In mid-December 2024, four other Guantánamo inmates — a Kenyan, a Tunisian, and two Malaysians, were transferred by the Biden administration to their home countries.

All of them were approved for transfer by national security officials more than two years ago, in October 2023, and sometimes long before that—one had been cleared for transfer since 2010—yet had remained behind bars due to political and diplomatic factors.

Trump administration used Guantánamo for migrant detention

On January 29, 2025, President Trump signed an executive order directing the expansion of detention operations for “high-priority criminal aliens unlawfully present in the United States.” He suggested that 30,000 migrants could be held at Guantánamo.

Reporter Carol Rosenberg, who has covered Guantánamo prison and court proceedings since the first detainees were brought to the U.S. base in 2002, has written on the use of the U.S. Naval Base by ICE to house migrants.

Since the Migrant Detention Center was set up on the U.S. Naval Base, Guantánamo, Cuba, in February 2025, around 700 foreign citizens have been held there awaiting deportation. The center was established to hold tens of thousands of unauthorized immigrants in tent cities.

Thankfully, the tent city never reached that capacity, with the largest number of migrants held there on a single day being 178 on February 19, 2025. They were all Venezuelans, and all but one were deported back to Venezuela.

Since February 19, the deportee population has ranged from a single migrant to dozens. At the end of July, 61 people were being held at Guantánamo in the custody of Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents.

Since then, 16 ICE flights have picked up deportees to either return them to the United States or add to flights already loaded with other migrants and continue to other countries.

According to Thomas Cartwright, who tracks deportations with the immigrant rights group Witness at the Border, their destinations included Colombia, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, England, Guatemala, Honduras, India, Laos, Nigeria, Romania, St. Kitts, Sierra Leone, and Vietnam.

In June 2025, lawyers from the American Civil Liberties Union (the ACLU), the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) and the International Refugee Assistance Project (IRAP) filed a class action lawsuit. Luna Gutierrez v. Noem argues on behalf of two Nicaraguan nationals who were held at Guantánamo at the time, but also on behalf of every other migrant in “a similarly situated class, namely, “all immigration detainees originally apprehended and detained in the United States, and who are, or will be held at Naval Station Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.”

On September 25, 2025, 18 men who were the last migrants awaiting deportation from Guantánamo prison were flown by ICE officials back to the United States.

On December 5, 2025, ten months after migrants with final deportation orders began being sent to Guantánamo Naval base for detention, Judge Sparkle L. Sooknanan from the District Court in Washington, D.C. ruled that the Trump administration’s policy of holding migrants at Guantánamo was both “impermissibly punitive,” as a violation of the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause, and was also completely unauthorized under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA).

So far, the Trump administration has not attempted to send migrants to Guantánamo in the month since Judge Sooknanan’s ruling.

Costs of the Guantánamo prison are mostly incalculable

There are many costs for the U.S. prison at the U.S. Naval Base near Guantánamo, Cuba.

The psychological and physical cost to each person who has been imprisoned in Guantánamo is incalculable and will last the rest of the lives of those who were imprisoned there, as well as to their families.

The cost to the reputation of the United States after the scenes of torture and of the extrajudicial treatment of prisoners by military courts instead of civilian courts is also incalculable.

Each inmate held in Guantánamo now costs American taxpayers an estimated $15million a year, compared to about $80,000 annually per inmate at a U.S. supermax facility.

500 U.S. federal prisoners are serving major sentences for terrorist-related offences and are housed in dedicated Supermax prisons. This includes the shoe bomber, the underwear bomber, the Boston Marathon bomber, and the so-called twentieth hijacker.

In February 2025, the closing of Guantánamo prison should have been at the top of the list for the DOGE money-savings, but in a rare show of bipartisanship, Congress has prohibited any Guantánamo detainee from being brought to the United States for trial or imprisonment.

Ann Wright served 29 years in the U.S. Army/Army Reserves and retired as a Colonel. She was a U.S. diplomat for 16 years and served in U.S. Embassies in Nicaragua, Grenada, Somalia, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Sierra Leone, Micronesia, Afghanistan, and Mongolia. She resigned from the U.S. government in March 2003 in opposition to the U.S. war on Iraq. She is the co-author of “Dissent: Voices of Conscience.”