This is the second part of an eight-part series telling the stories of all the prisoners currently held in Guantánamo (174 at the time of writing). See the introduction here, and the first part here.

This second article tells the stories of 27 prisoners seized in Afghanistan, mostly in December 2001. A handful are reportedly significant figures in the Taliban, and most of the rest were either transferred to US custody after a massacre in a fort in the northern Afghan city of Mazar-e-Sharif, or were seized after the Battle of Tora Bora, a showdown between al-Qaeda and US forces in the mountains near Jalalabad.

Noticeably, only a few are accused of any serious involvement with al-Qaeda or terrorist activities (although these claims are themselves dubious), and three others have lost their habeas corpus petitions. It is also worth remarking that the majority of the men discussed in this chapter are Yemenis, and that many have presumably been cleared for release by President Obama’s Guantánamo Review Task Force, but are waiting to see if the President will, at any point the future, lift the unprincipled moratorium on transfers to Yemen that he announced in January.

ISN 004 Wasiq, Abdul-Haq (Afghanistan)

Reportedly the Taliban’s deputy minister of intelligence, he was seized in a Special Forces operation in Ghazni in December 2001, with Gholam Ruhani (released in December 2007). However, in his review board at Guantánamo in 2005, he claimed that “he was attempting to assist the US in capturing Mullah Mohammed Omar.”

ISN 006 Noori, Mullah Norullah (Afghanistan)

Noori was reportedly the governor of Balkh province under the Taliban, and according to press reports at the time, helped Mullah Mohammed Fazil (see ISN 007, below) negotiate the surrender of Kunduz, the last Taliban stronghold in the north of Afghanistan, with General Rashid Dostum of the Northern Alliance in November 2001. In Guantánamo, he played down his role, describing himself not as “a member of the Taliban,” but as a “soldier with them,” who had joined them in 1999. However, in a summary of evidence in January 2007, the US authorities clearly identified him as a significant figure in the Taliban.

ISN 007 Fazil, Mullah Mohammed (Afghanistan)

Reportedly the Taliban’s deputy defense minister, press reports in November 2001 stated he led the negotiations with General Dostum for the surrender of Kunduz. Both he and Noori surrendered to Dostum and were then kept under informal house arrest until they were handed over to US forces. In other reports at the time, Mohammed Muhaqiq, a leader of the Hazara, the ethnic group most persecuted by the Taliban, suggested that a number of Taliban leaders, including Noori and Fazil, should be prosecuted for war crimes, including ethnic cleansing. Like Noori, he tried to play down his role, but in a summary of evidence in October 2007 it was stated that approximately 3000 Taliban troops were under his control in October 2001.

ISN 088 Awad, Adham Ali (Yemen)

Seized after a group of al-Qaeda soldiers besieged in a hospital surrendered him to the Afghan authorities in December 2001, Awad, who was just 19 years old at the time, stated that he had been wounded in a bombing raid while walking through a market in Kandahar, but lost his habeas corpus petition in August 2009, when Judge James Robertson accepted what he described as a “gossamer thin” case put forward by the government. In June 2009, his appeal was denied by the D.C. Circuit Court.

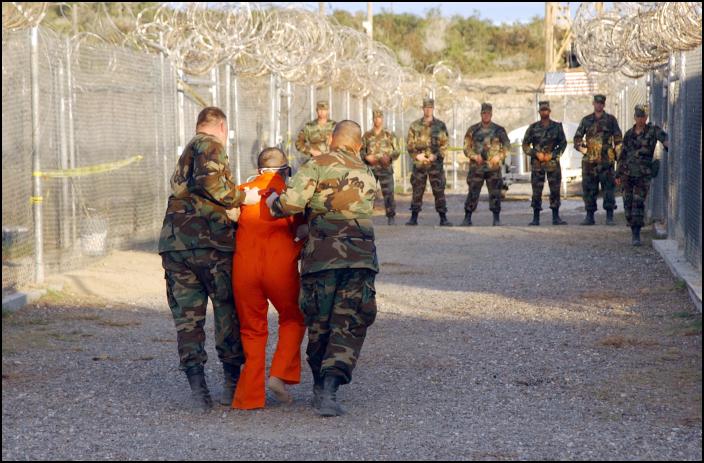

The following seven prisoners survived the Qala-i-Janghi massacre in November 2001, which followed the surrender of the northern city of Kunduz, when several hundred Taliban foot soldiers, who had been told that they would be allowed to return home if they surrendered — and, it seems, a number of civilians — were taken to a fortress run by General Rashid Dostum of the Northern Alliance. Fearing that they were about to be killed, a number of the men started an uprising, which was suppressed by the Northern Alliance, acting with support from US and British Special Forces, and US bombers. Hundreds of the prisoners died, but around 80 survived being bombed and flooded in the basement of the fort, and around 50 of these men ended up at Guantánamo. All but these seven have been released.

I

SN 091 Al Saleh, Abdul (Yemen)

In Guantánamo, al-Saleh said that he had answered a fatwa calling for young men to travel to Afghanistan, but felt that “the Taliban cheated him because he was fighting the Northern Alliance, which was not a cause that he believed in; therefore, it was not really a jihad for him.” He also denied knowing any members of al-Qaeda, and stated that, if returned to Yemen, he would “get married” and would “disregard anyone who suggests that he fight jihad.”

ISN 115 Naser, Abdul Rahman (Yemen)

Naser was accused of arriving in Afghanistan in January 2001 and fighting on the Taliban front lines for six months at Khawaja Ghar, prior to his capture. It was also stated that, in Guantánamo, he had been “cited for numerous incidents of failure to comply, guard harassment, assault, and inciting of disturbances during his detention.” However, it was also noted that he “denie[d] seeing Osama Bin Laden while in Afghanistan,” and “stated that if he were released, he would return home to the family farm and get married.”

ISN 117 Al Warafi, Mukhtar (Yemen)

Al-Warafi had his habeas corpus petition denied in March 2010 by Judge Royce C. Lamberth. Al-Warafi claimed that he had traveled to Afghanistan to work as a medic, and had tended wounded Taliban fighters at a clinic in Kunduz, but Judge Lamberth denied his habeas petition not only because he believed that he had been acting as part of the Taliban’s “command structure,” but also because Congress had removed the Geneva Conventions’ requirement not to imprison medics when passing the Military Commissions Act in 2006, which cynically stated, “No person may invoke the Geneva Conventions … in any habeas corpus proceeding … as a source of rights in any court of the United States.”

ISN 128 Al Bihani, Ghaleb (Yemen)

Al-Bihani had his habeas corpus petition denied in January 2009 by Judge Richard Leon. He had worked as a cook for Arab forces supporting the Taliban, and Judge Leon concluded that this met the definition of “support” for al-Qaeda or the Taliban that justified his detention. He explained that “faithfully serving in an al-Qaeda-affiliated fighting unit that is directly supporting the Taliban by helping prepare the meals of its entire fighting force is more than sufficient to meet this Court’s definition of ‘support,’” and added, “After all, as Napoleon was fond of pointing out, ‘An army marches on its stomach.’” Al-Bihani appealed, but his appeal was denied by the D.C. Circuit Court in January 2010, in a ruling in which the court claimed that his argument that “the war powers granted [to the President] by the AUMF [the Authorization for Use of Military Force] and other statutes are limited by the international laws of war” was “mistaken.”

ISN 131 Ben Kend, Salem (Yemen)

Ben Kend (also identified as Salem Ahmed Hadi) reportedly fought on the Taliban front lines for six months, prior to his capture. However, in a statement prepared for a review board in 2006, he stated that he was “shocked” to see an allegation that he had “fought with the Taliban in Kabul and in Kandahar from July 2001 to December 2001.” Leaving aside the fact that he was seized in November 2001, he “responded that he did not fight in Kandahar, although he was in the area.”

ISN 202 Bin Atef, Mahmoud (Yemen)

Bin Atef is accused of arriving in Afghanistan for jihad in June 2001, training at al-Farouq, and fighting on the Taliban front lines. In an interrogation, he apparently stated that “his enemies were the Northern Alliance,” and also stated that “he never shot at or killed anyone,” and that, although he “was asked to take an oath to Osama bin Laden, [he] did not take one since he might have been obligated to do things that he might not want to do.”

ISN 434 Al Shamyri, Mustafa (Yemen)

He reportedly fought with the Taliban for ten months after answering a fatwa. One unidentified source claimed that he was “a trainer at al-Farouq,” and another allegation stated, implausibly, “Indications are that the detainee was a commander of troops at Tora Bora” (this was impossible, as he was captured before the battle of Tora Bora). One other allegation in particular — that “A detained al Qaida official identified [him] as a Yemeni national who participated in the Bosnian Jihad” — is unlikely, as he would have been only 15 or 16 years old at the time. It was also claimed that, in Guantánamo, he “was cited for harassing guards, inciting disturbances and several hostile acts.”

ISN 440 Bawazir, Mohammed (Yemen)

Bawazir may have been present at Qala-i-Janghi, but he denied it. As I explained in The Guantánamo Files, he also denied claims that he trained at al-Farouq and fought with the Taliban, stating that he traveled to Afghanistan to provide humanitarian aid, and also spent time visiting the front lines with a religious figure who used to ask the soldiers if the knew why they were fighting, stating, “Religion is not all about fighting.” He claimed that all the allegations against him — including a claim that he attended Osama bin Laden’s daughter’s wedding in Kandahar — came about because he was tortured. “When I came to Mazar-e-Sharif they questioned me [and asked] me if I was from al-Qaeda,” he said. “They used to hit me physically until they broke my skull … Then I had to say yes I had met Osama bin Laden, that I talked with the Taliban, that I knew about nuclear rockets, and that I know everything about what al-Qaeda is up to.” In 2005, Bawazir embarked on a hunger strike (the largest of many throughout the prison’s history), which involved painful force-feeding, and at one point his weight dropped to just 100 pounds. In November 2009, he petitioned the D.C. District Court to declare that force-feeding was “tantamount to torture,” but Judge Gladys Kessler ruled that she did not have the “appropriate expertise” to decide whether that was true.

ISN 441 Al Zahri, Abdul Rahman (Yemen)

In statements at Guantánamo, al-Zahri apparently admitted traveling to Afghanistan in the hope of fighting in Chechnya, but ended up fighting against the Northern Alliance, when he was wounded and subsequently seized by US forces. He may have been at Qala-i-Janghi, although this is not clear, and he has also provided conflicting accounts of his allegiances, on occasions mentioning his admiration for al-Qaeda and claims that he met Osama bin Laden on several occasions, and on one other occasion denouncing bin Laden “as a heretic, who attacked civilians — in violation of the laws of Islam.”

ISN 461 Al Qyati, Abdul Rahman (Yemen)

Al-Qyati, who was cleared for release by a military review board under President Bush, reportedly traveled to Afghanistan in May 2001, trained at al-Farouq, and was a guard “for 39 high-level Taliban personnel” at Kandahar airport, where he was seized in November 2001. According to his habeas corpus petition, submitted in December 2008, although listed as a Yemeni, he was “born and raised in Saudi Arabia and has never lived in, or even traveled to Yemen.”

The following 13 prisoners were mostly captured around the Tora Bora region in December 2001, following a showdown between al-Qaeda (and Taliban forces supporting them), and the US, which provided bombers to back up a military campaign that was primarily conducted by Afghan forces. Notoriously, the US allowed Osama bin Laden and other senior leaders of al-Qaeda and the Taliban to escape from Tora Bora. Around 50 men seized at this time ended up in Guantánamo, although it is by no means certain that all of them had been involved in the conflict. Around three dozen of these prisoners have already been released.

ISN 498 Haidel, Mohammed (Yemen)

In Guantánamo, Haidel stated that he traveled to Afghanistan “to get married and for a change of environment.” The US authorities alleged that he trained at al-Farouq, was sent to the front lines in Kabul, and was then driven with other fighters, to Tora Bora, where, he said, “he sat in a cave for fifteen days,” and was then injured by a bomb blast, captured by the Northern Alliance and taken to a prison in Kabul, before being handed over to the Americans. In response to an allegation that he received mortar training, Haidel said, “When I was in the Kandahar prison, the interrogator hit my arm and told me I received training in mortars. As he was hitting me, I kept telling him, ‘No, I didn’t receive training.’ I was crying and finally I told him I did receive the training. My hands were tied behind my back and my knees were on the ground and my head was bleeding. I was in a lot of pain, so I said I had the training. At that point, with all my suffering, if he had asked me if I was Osama bin Laden, I would have said yes.” A long-term hunger striker at Guantánamo, Haidel weighed just 105 pounds on arrival in May 2002. In November 2002, his weight dropped to just 90 pounds, and at the time that the Pentagon’s declassified weight records came to an end, in November 2006, he weighed just 102 pounds.

ISN 502 Bin Ourgy, Abdul Bin Mohammed (Tunisia)

Formerly an Italian resident, bin Ourgy, who was cleared for release from Guantanamo by a military review board under the Bush administration, stated that he traveled to a training camp in Afghanistan in 1997 that was unconnected to al-Qaeda, and that he married an Afghan woman in 2000. A “senior al-Qaeda lieutenant” accused him of being an explosives expert, who was at Tora Bora, and was also involved in the assassination of Ahmed Shah Massoud, the leader of the Northern Alliance, on September 9, 2001, but these allegations are, of course, untrustworthy, as they may have been extracted through the use of torture. In July 2009, it was suggested that he might be transferred to Italian custody, to face a trial. The Italian media reported that he was “suspected of having had links in Milan with people who sought volunteers to fight in Iraq and Afghanistan with Islamic insurgents,” but in December 2009, when two other Tunisians were transferred to Italian custody, he remained in Guantánamo.

ISN 506 Al Dhuby, Khalid (Yemen)

Allegedly recruited for military training in Afghanistan after being shown videos of atrocities in Chechnya, al-Dhuby reportedly arrived at al-Farouq in late July 2001, and trained for a month and a half until the camp closed. He was then taken to Tora Bora, where he “stayed in one of several caves large enough to fit three or four people,” and then left the area with a group of other men. He said that as they passed through a valley he “saw planes dropping bombs on their location and stated the bombing went on for one night,” and added that he “hid from the bombs until the next morning,” but that many of the men traveling with him “were killed and injured by the bombing.” After the bombing, he was seized by Northern Alliance soldiers and held in an Afghan prison in Kabul before being handed over — or sold — to US forces. At Guantánamo, he maintained that he had never fired a shot at anyone, that he “was not a fighter or a killer,” and that he only “wanted to train to protect himself and his family as well as defend his country.”

ISN 508 Al Rabie, Salman (Yemen)

In Guantánamo, the authorities could not initially decide whether they thought al-Rabie (also identified as Salman Rabeii), who was 20 years old at the time of his capture, had been seized in Tora Bora, or in Jalalabad, as he claimed. By 2006, they decided that he had attended al-Farouq in August 2001, and that he was captured “coming out of the Tora Bora mountains” on December 16, 2001 “after surrendering to Afghan forces.” In October 2006, however, his father told Gulf News that Salman had only traveled to Afghanistan in search of his brother, Fawaz. “I sent Salman to look for his brother and bring him back from Afghanistan, but the war broke out and he could not come back. He was detained and put in Guantánamo,” he said.

ISN 509 Khusruf, Mohammed (Yemen)

As I explained in The Guantánamo Files, Khusruf, who was seized after a bombing raid in the Tora Bora region, said that he went to Afghanistan to teach the Koran, and asked, “Is it really reasonable that al-Qaeda or the Taliban, in bad need of men to fight, have to go to Yemen to find men at 60 years old to fight? Is this logical?” (according to US records, he was actually 51 years old at the time of his capture). He admitted training at al-Farouq, but said that he only did so because the man who arranged his travel told him he needed to be able to defend himself. He also explained that, after his arrest, he was moved from a jail in Jalalabad to “an underground prison” in Kabul — possibly the CIA’s “Dark Prison,” or else an Afghan jail — where “they would interrogate and beat us.” He added that those who were wounded “were also there” — presumably some of the other men rounded up in the Tora Bora region, who also ended up in Guantánamo.

ISN 511 Al Nahdi, Sulaiman (Yemen)

Cleared for release by a military review board under the Bush administration, al-Nahdi lost his habeas petition in February 2010, when Judge Gladys Kessler ruled that he had “entered into the ‘command structure’ of al-Qaeda during his travel from Pakistan to Afghanistan, during his attendance at al-Farouq, and through his role as a guard at Tora Bora, even though these demonstrations of his involvement in the “command structure” actually demonstrated how generally insignificant he was. As I explained at the time, “In a review board at Guantánamo, he explained that the leaders of al-Farouq ‘ordered us to move from one place to another. They told us to go to Tora Bora so that is where we went.’ Judge Kessler also noted that al-Nahdi had stated that ‘[a]t the time, you could not ask them why and where you were going. You cannot refute them. You had to do what they told you to do.’”

ISN 522 Ismail, Yasin (Yemen)

In April 2010, Ismail, who may have been just 19 when he was seized, lost his habeas petition when Judge Henry H. Kennedy Jr. refused to accept his claim that he had been kidnapped in Kabul by Afghans and taken to Tora Bora, where he was sold to US forces, and concluded instead that he had trained at al-Farouq and had traveled to Tora Bora as a fighter, like Sulaiman al-Nahdi. Nevertheless, it is far from reassuring that, throughout his time in US custody, he has alleged that he was tortured and subjected to sexual humiliation, and that he has been subjected to regular assaults by the Immediate Reaction Force (IRF), teams of five soldiers who respond to the most minor infractions of the rules with brutality.

ISN 535 El Sawah, Tariq (Egypt-Bosnia)

The last prisoner put forward for a trial by Military Commission under President Bush, El-Sawah, now 52 years old, is a veteran of the Bosnian conflict, who had married a local woman and had then traveled to Afghanistan, where he became an explosives expert at al-Farouq. Ferociously opposed to the Northern Alliance, but not to the US, he apparently became one of the most useful informers within Guantánamo, according to an article in the Washington Post in March 2010, which explained that, according to a former military intelligence official, “He was an old-soldier type who’d just had a bellyful. Right after he got to Guantánamo, he told the interrogators he’d had it,” and he became “the source of 150 first-rate information reports.”

Former prisoners dispute this account, questioning El-Sawah’s mental health, and the quality of his information, but it has led to a strange situation for El-Sawah and Mohamedou Ould Slahi (ISN 760), who, unlike El-Sawah, was tortured until he decided to start talking (and whose value as an informer is therefore suspicious as well). As “two of the most significant informants ever to be held at Guantánamo,” in the Post’s words, they live in “a little fenced-in compound,” allowed to write, in Slahi’s case, and to paint, in El-Sawah’s case. As the Post also explained, “Each has a modular unit outfitted with a television. Each has a well-stocked refrigerator. They share a garden, where they grow mint for tea.” However, notwithstanding doubts about the quality of their evidence as informers, the Post article pertinently pointed out how shabbily informers are treated in the post-9/11 world, explaining, “Some military officials believe the United States should let them go — and put them into a witness protection program, in conjunction with allies, in a bid to cultivate more informants,” and quoting W. Patrick Lang, a retired senior military intelligence officer, who said, “I don’t see why they aren’t given asylum. If we don’t do this right, it will be that much harder to get other people to cooperate with us. And if I was still in the business, I’d want it known we protected them. It’s good advertising.”

ISN 549 Al Dayi, Omar (Yemen)

Al-Dayi, who weighed just 98 pounds when he arrived in Guantánamo, is accused of traveling to Afghanistan in August 2001. It is also alleged that he stayed at a safe house in Kandahar, but became ill with malaria after one day, and “had trouble standing and walking,” and that, after six weeks at the safe house, he and others in the house were told to go to Jalalabad, where they stayed in another safe house for a few weeks before leaving for Tora Bora. In the mountains, it was alleged that al-Dayi “was shown to his position,” with 10-12 other Arabs, but that his group, though armed, “spent most of its time hiding in one of the three caves located close to its position.” Wounded in the leg by a missile, he was then “evacuated by an Afghan on a donkey to a nearby village,” and driven to the hospital in Jalalabad, where he stayed for two months “before being taken by Americans to a prison in Kabul” — presumably the “Dark Prison” — before his transfer to Guantánamo.

ISN 550 Zaid, Walid (Yemen)

As I explained in The Guantánamo Files, Zaid, who was wounded in the left foot in an air raid in the Tora Bora region, and was then hospitalized in Jalalabad before being handed over — or sold — to US forces, denied that he went to Afghanistan for “Jihad readiness military training,” as alleged, and said that he had just finished his final year studying Arabic literature at college, and went to Afghanistan a fortnight before 9/11 because he hoped to teach Arabic in an Afghan school. He admitted attending al-Farouq, but said that he had only done so because some Afghan acquaintances said that Afghanistan “was a country with a great deal of fighting,” and suggested that he should get some training in self-defence. At other times, he appears to have conceded that he traveled to Afghanistan to support the Taliban, but he has maintained that he “harbors no ill will towards the United States” and “only wishes to return home and put this part of his life behind him.”

ISN 552 Al Kandari, Fayiz (Kuwait)

A Kuwaiti from a wealthy family, with a history of humanitarian work, al-Kandari has always maintained that he was a humanitarian aid worker who arrived in Afghanistan in August 2001, was caught up in the chaos following the 9/11 attacks and the US-led invasion of October 2001, and was seized by Afghan forces and sold to the US military in December 2001, as he tried to cross the mountains to Pakistan. Despite this, the US authorities allege that between August and December 2001, he somehow managed to attend al-Farouq, “provided instruction to al-Qaeda members and trainees,” “served as an adviser to Osama bin Laden,” and “produced recruitment audio and video tapes which encouraged membership in al-Qaeda and participation in jihad.” The authorities took these allegations so seriously that, in November 2008, he was put forward for a trial by Military Commission, although the charges have not been revived under President Obama. Sadly, the US authorities seem to have encouraged themselves to believe that al-Kandari is significant because he has been particularly resistant to the pressure to cooperate and has steadfastly refused to make false statements about himself or about anybody else. Over the years, he has been subjected to a vast array of “enhanced interrogation techniques,” which, as his military defense lawyer, Lt. Col. Barry Wingard described them, “have included but are not limited to sleep deprivation, physical and verbal assaults, attempts at sexual humiliation through the use of female interrogators, the ‘frequent flier program,’ the prolonged use of stress positions, the use of dogs, the use of loud music and strobe lights, and the use of extreme heat and cold.”

ISN 553 Al Baidhani, Abdul Khaliq (Saudi Arabia)

Also identified as Abdul Khaled al-Bedani, he was just 18 at the time of his capture, and, by his own account, arrived in Afghanistan with particularly unfortunate timing. He admitted that he was recruited to receive military training, but said that he was in a guest house in Kabul, awaiting training, when he heard about 9/11 and decided to leave Afghanistan immediately. As this was an impossible task for a teenager without a passport (like all other recruits, he was obliged to hand in his passport “for safekeeping” when he arrived), he ended up fleeing with other recruits to Tora Bora, where he shared a bunker with a number of armed men and was provided with a gun. Wounded during a bombing raid, he was “then picked up by local Afghans who turned him over to the Northern Alliance.” Although he had received no military training and insisted that he never fired a shot, his admission that he was “provided with a weapon” was sufficient for his tribunal at Guantanamo to decide that he had “participated in military operations against the coalition.”

ISN 554 Al Assani, Fehmi (Yemen)

Cleared for release by a military review board under the Bush administration, al-Assani, like Sulaiman al-Nahdi (ISN 511), lost his habeas petition in February 2010, when Judge Gladys Kessler ruled that he had “entered into the ‘command structure’ of al-Qaeda during his travel from Pakistan to Afghanistan, during his attendance at al-Farouq, and through his presence at Tora Bora, even though these demonstrations of his involvement in the “command structure” actually demonstrated how generally insignificant he was. As I explained at the time, there there was “something rather pathetic about al-Nahdi’s claim that many of the men at Tora Bora, ‘including himself, were scared, and only wanted to go home after the fighting began,’ and the report of his attempt to leave (which, Judge Kessler noted, demonstrated only that he “acted in proper ‘command mode’”), when he ‘asked his commander … if he could leave, and after being rebuked did not attempt to do so.’”

Andy Worthington is the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon.